UBS: Back to the 1990s? (10/04/2024)

“Be invested at all times” is our most important credo for investors. This is based on the assessment that we may be in an above-average productive phase of the global economy, further fueled by stimulating monetary policy and disruptive innovations. We draw a comparison to the golden 1990s. And: Back from the Venice Art Biennale, we report on a great installation by Swiss artist Christoph Büchel at the Palazzo Prada, which explores the secrets of guilt and debt in human history. Worth a visit.

1. Stock market history, then and now: A look at the 1990s

It seems that both the 1990s and the current stock market decade benefit from above-average productivity gains. This is due to two positive side effects of rising productivity: First, it increases profit margins and usually also the wages of employees. Second, it lowers prices, costs, and thus also inflation and interest rates. Let’s briefly consider some aspects of the 1990s:

Geopolitics

The Cold War ended with the fall of the Iron Curtain on May 2, 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, and the official dissolution of the former Soviet Union on December 25, 1991.

Francis Fukuyama's bestseller "The End of History" popularized the idea that liberal democracies had finally prevailed. Nothing symbolized this better than Nelson Mandela's peaceful takeover and the end of apartheid in South Africa on May 10, 1994.

The Second Gulf War (July 1990 to March 1991) demonstrated the geopolitical dominance of the US and changed the world to this day. It also left new North-South antagonisms in place of the former East-West tensions, as seen in the rise of the so-called BRICS countries (originally: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) around the turn of the millennium.

Stock markets and interest rates

In January 1990, there was a sense of optimism in the stock markets. "Black Monday," which had caused the Dow Jones Index (DJIA) to crash by 22.6 percent in a single day on October 19, 1987, was already more than two years in the past. Since then, the DJIA has recovered from 1,800 to 2,590 points.

US unemployment was still 6.3 percent in 1990. However, for the first time in the early 1990s, the Federal Reserve confirmed that it considered interest rates its most important monetary policy tool. Between July 1990 and September 1992, it lowered interest rates at every meeting, from 8 to 3 percent in total. This created a powerful, sustained tailwind for the economy and markets. By the end of the 1990s, interest rates were back at 6 percent, but in the meantime, a strong economy had carried the DJIA to over 10,000 points.

Technology

Around 1990, Tim Berners-Lee invented the first web browser at CERN in Geneva. It was a breakthrough with revolutionary second- and thirdround effects. The internet, email, and online shopping lowered prices, costs, inflation, and interest rates. The costs of long-distance communication fell permanently to near zero. This led to many productivity innovations for companies.

Pioneers of their time like Nokia, Ericsson, and Cisco brought mobile telephony, SMS, and video conferencing into everyday life. They replaced business trips and favored the emergence of virtual organizations. There were many other pioneers who achieved great things with small inventions. Three examples:

In 1991, the Swiss IT company Logitech launched the first digital cameras. It was the beginning of a new era.

In 1994, Jeff Bezos founded Amazon, a disruptive online retailer that shipped books to 50 US states and 45 countries in its first month. Today, the world's fifth-largest company by market capitalization, with over one and a half million employees, exemplifies the revolution in online business.

In 1998, Larry Page and Sergey Brin founded the search engine Google, revolutionizing global access to knowledge via the internet. Today, Google is the fourth-largest company in the world by market capitalization and employs more than 180,000 people.

Productivity

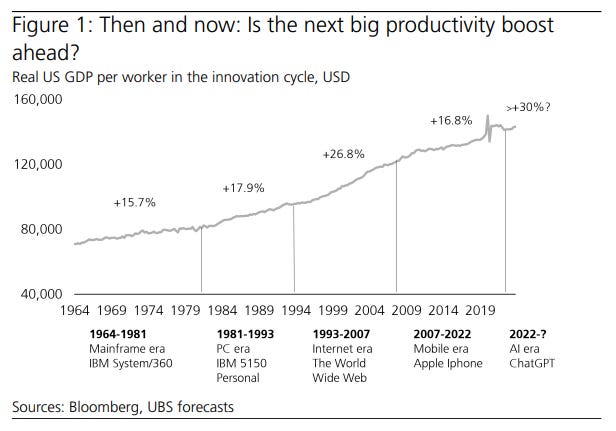

The success of many innovations was based on reducing costs while creating new quality levels. This led to a major productivity boost. Between 1993 and 2007, US worker productivity, measured by real GDP per worker, increased by more than +26 percent while keeping inflation in check despite a strong economy. A post-war record that triggered a golden stock market era.

Euphoria and crash

By the end of the 1990s, there was too much of a good thing. Stock market success turned into euphoria. The difference between investing and speculating was forgotten. TV shows turned the stock market into a spectacle, and the euphoric bubble was palpable. Between 1995 and 2000, the Nasdaq quintupled. The explosively growing Frankfurt “Neuer Markt” (Nemax) almost tenfolded between January 1998 and March 2000.

Then the stock market bubble burst, destroying dreams and capital. Small investors were particularly affected. The Dow Jones lost about 30 percent between April 2000 and September 2002, the Nasdaq lost almost 80 percent, and the Nemax lost practically everything—including its good reputation due to numerous fraud cases among index companies. It was abandoned in June 2003.

2. Parallels and points: Why investors should stay invested

Let's draw some comparisons between then and now:

The upcoming AI revolution

From the perspective of the economy and markets, we are at the beginning of even more radical developments than those triggered by the introduction of the internet around 1990. Back then, communication costs fell to near zero, changing many business models and triggering a productivity boost. Today, it is artificial intelligence (AI) that is driving the costs of evaluating world knowledge to near zero. The potential uses of this new development are numerous.

Two statistics for illustration: NVIDIA's over USD 25,000 Blackwell chip, the size of a matchbox, contains the almost unimaginable number of 208 billion transistors. It can perform 20 quadrillion calculations per second. In other words, the computing power of today's Blackwell chip is about 20,000 times higher than that of IBM's “Deep Blue” which first defeated world chess champion Garry Kasparov in 1997. The million-dollar computer was rightly considered a revolution in 1997, linking the then-record sum of 1.5 million transistors.

In the coming years, representatives from various economic, technological, and life sectors are likely to make use of the new availability of world knowledge. With AI, they could have the most powerful tool in history at their disposal. They may seek answers to practically all the big questions of our time—and in many cases, they may find them. Unlike Google searches, which only deliver websites and text documents, AI also evaluates this information. And if “time is money” then these advances in seeking answers to the big questions of our time are certainly worth a lot of money.

Incidentally, rising electricity costs for AI are also likely to be relativized soon —either by developing more efficient chips or, at the latest, when the costs of generating certain energies, like solar or wind, fall to near zero.

At the beginning of a long rate cut

With the Fed's recent move, we believe interest rates have begun their retreat. Similarly, falling interest rates created a powerful tailwind at the beginning of the 1990s.

But a critical view is also possible here. Has the Fed overshot the mark by stimulating a strong US economy? Could the next surprise be a “melt up” as a result—similar to the late 1990s? A difference between then and now lies in the level of euphoria. Rather, the healthy balance sheets of the private sector minimize this risk.

The world as a village

The internet turned the world into a village. Globalization has brought it even closer together. On the stock markets, China's recent stock rally illustrated how everything is interconnected. The US interest rate decision likely gave the Chinese central bank the opportunity to also implement stimulus measures without devaluing its own currency. Whether China's stock rally is a flash in the pan or lasting remains to be seen.

In our UBS House View, we have not changed the recommended China allocation in global portfolios and maintain a preference for large Chinese tech companies—emphasizing the timeless value of global diversification.

Dow Jones 60,000 in 2030?

Since 1950, the average performance of the DJIA has been +8.5 percent per year. During the 1990s, the productivity boost lifted it even higher, creating a golden era for investors. A similar development could be possible in the current decade. With annual average growth of 8.5 percent, the DJIA would mathematically increase by about 50 percent from its current level of around 42,000 points over the next five years—reaching over 60,000 points by 2030. But of course, mathematically speaking does not mean reality. While we do see a constructive outlook,1 risks abound in the global economy—from wars to slowing growth. Still, the traditional year-end rally may have already begun. A comparison of the two decades is certainly insightful.

3. The world in pawn: Christoph Büchel's "Monte di Pietà" installation in Venice

This installation alone makes a trip to the current Venice Art Biennale worthwhile, which I visited last weekend. You can immerse yourself for hours in the double-edged irony of its allegories. The 18th-century palazzo, which Swiss artist Christoph Büchel has ostensibly transformed into a temple of trash under the banner of an "Everything Must Go" liquidation, served as a branch of the once widespread credit institution "Monte di Pietà" ("Mount of Mercy") from 1834 to 1969. Today, it houses the highly esteemed Prada Foundation in the art world, which demonstrates greatness with this selfcritical exhibition.

"Monte di Pietà" functions like a quirky, multi-layered, sensitive, and intelligent cabinet of curiosities. There is much to discover on three floors and in over twenty rooms. It is a thousandfold world, consisting of symbols, quotes, and found objects. Right at the entrance is a doorbell panel with the sign "D. Graeber." A hidden reference to the American cultural anthropologist David Graeber, who died in Venice in 2020 and made a name for himself as the author of the much-acclaimed book "Debt: The First 5000 Years," as well as a later co-initiator of the "Occupy Wall Street" movement.

But before we delve into the complex connection between guilt and debt in human history on the top floor, the entrance to the building is already astonishing. Instead of entering the palace of our dreams, we step into a cheap pawnshop, as once located here under the ironic name "Queen of Pawn. House of Diamonds." We see shattered ATMs, empty shelves of a "Banca Alimentare," a Golgotha hill of trash, a dressing table with tips, a chessboard, an ashtray, and a blaring TV broadcasting an art auction. Next to it is an old magazine featuring Miuccia Prada, the current owner. A manifesto of the anti-Biennale movement testifies to the civil resistance of Venetian citizens who feel sold out by an unholy alliance of "overtourism," art, politics, and commerce.

In "Monte di Pietà," everything happens casually, much is only revealed at second glance. In the fresco-adorned "Piano Nobile," the noble floor, we initially discover a lot of knick-knacks. But the smuggled-in artworks make us pause. A portrait of Caterina Cornaro by Titian from the Uffizi has found its way here, as well as a chalk-marked blackboard on the "Extended Concept of Art" by Joseph Beuys. Artistic references to money and pawn can be found from Marcel Duchamp, Edward Kienholz, or John Baldessari—alongside the successful reality TV show "Pawn Stars." As we rub our eyes from room to room, Büchel's cabinet of curiosities opens up an almost inexhaustible network of historical, socio-economic, and artistic correspondences on the themes of guilt and debt, art and commerce, power and repression. The fact that the artist never patronizes, does not judge, and does not present a dry thesis, but rather offers a rich and enjoyable tour de force through world, financial, and art history, sublimates the exhibition. It deserves top marks for combining a convincing formal language to address the big questions of our time. In the best case, art can make an important contribution to social discourse. Bravo.